Line drawing of ‘Marat: 13 July 1793’ by Eyre Crowe (1879), published in Henry Blackburn’s Academy Notes, No. 5, May 1879, p. 35

Medium: oil

Size: 35 x 27 inches

Exhibited: Royal Academy, 1879

Original caption: ‘Charlotte Corday, who had tried vainly two or three times to get admitted to see Marat, was overheard by him asking for an interview and he ordered her to be called in … When she entered the room he elicited from her the names of Girondist deputies at Caen. He then said, “They will soon all be guillotined”. Charlotte Corday then stabbed him with a knife, etc.’

The Examiner, 5 April 1879

.. we are enabled to see what work is in hand, and how our painters have progressed during this exceptionally murky winter, which has been almost as fatal in an artistic as in a sanitary sense, for many painters have been unable to finish their pictures owing to the wretched light … Mr. Eyre Crowe [is represented] by “Marat in his Bath” (July 13, 1793), while Charlotte Corday is coming in at the door, and a “Study of Bluecoat Boys.”

The Spectator, 3 May 1879:

… Marat is once more killed by Charlotte Corday, in a work by Mr. Eyre Crowe, A., of which we can only say that it is the most ugly and unpleasant version of the story which we have yet seen.

Daily Telegraph, 6 May 1879

Mr. Eyre Crowe A.R.A.’s (301) picture of “Marat” is a strikingly original, dramatic and thoughtful work. The gloomy tragedy of the act of assassination has occupied the attention, time and again, of numbers of the most distinguished foreign painters. Marat and Charlotte Corday have indeed been well-nigh as great favourites with the artists as Judith and Holofernes, Jael and Sisera, and Salome with the head of John the Baptist have been. But Mr. Eyre Crowe has with great dramatic skill shown us the scene and the characters in the Maratian drama prior to the catastrophe. The Man of Blood is lying in his bath, with a bit of planking placed crosswise for a desk, busied with his newspapers and his voluminous correspondence. He may be correcting the proofs of some ferocious leading article in the Ami du Peuple, yelling for the heads of more “aristos”. Charlotte Corday has made several ineffectual attempts to see Marat. At length he hears her voice, and he gives orders that she shall be called in. She enters and converses with him. He elicits from her the names of a number of Girondins who have taken refuge at Caen. “They will soon all be guillotined,” says the Man of Blood as he jots down the names of his intended victims. And then —-, Mr. Eyre Crowe discreetly drops the curtain. He is as judicious as a Greek writer of tragedy. Clytemnestra must not do her deed on the stage. Agamemnon must be slain in the side-scenes. The arrangement of Mr. Eyre Crowe’s picture is curiously angular, but most subtle in its accuracy. The austerity of his execution is at once compensated for by the suddenness and strength with which he grasps the perception of the spectator. That hideous man really seems to be the human-hyena wallowing in his tub, and yet all adry for more human gore. That really seems to be a door of wood which is opening, that a girl of real flesh and blood that is entering. You almost feel moved to turn your head away, shuddering lest you should see the girl’s arm uplifted, the knife glitter, the deathdoing blow fall.

Illustrated London News, 17 May 1879:

… Returning to the remaining works by R.A.’s or A.R.A.’s, we have to note no novelty of subject or treatment; unless it be in the case of Mr. Eyre Crowe, who represents the Duc d’Enghien cutting off, just before his execution, a lock of his hair for his secretly married wife (943), and Charlotte Corday about to enter the bath-room of Marat (301) – in both cases the unpleasantness of the themes being aggravated by excessive grimness of treatment.

Athenaeum, 31 May 1879:

Marat – 13th July, 1793, is a good design for a subject which has been painted in France a great deal too often, and sufficiently often in England. Marat sits in his bath, writing on a board placed before him. Charlotte Corday, not looking like the inspired heroine whom the Parisian artists depict, pushes open the door at Marat’s call and enters the room. Mr. Crowe has avoided the murder and its accompaniments, and he has represented the light of the room and the numerous accessories with care and skill, so that we may fully depend on them. Is Marat old enough?

Art Journal, August 1879:

The more important figure pictures in the room are the stabbing of Marat by Charlotte Corday (301), from the able pencil of Eyre Crowe, A., and the ‘No Surrender’ (324) … by Andrew C. Gow. There is perhaps a little dryness in Mr. Crowe’s treatment; but both are remarkably able works, and we regret that want of space prevents out lingering over their excellences.

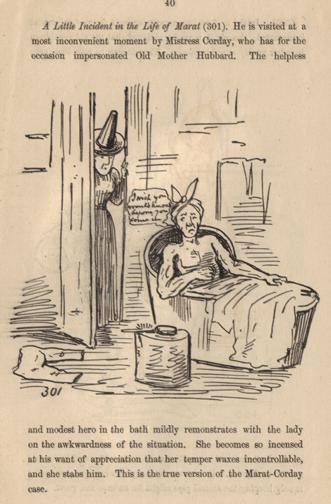

The painting was mercilessly spoofed in an illustrated satire of the Royal Academy Exhibition published in the same year.